Police agencies often publicize their ‘general deterrence’ approach to reducing traffic offending and reducing road trauma. A singular focus on ‘general deterrence’ which is often focused on ‘highly visible’ enforcement is part of, but not the whole solution. It is important to recognize the need for both general and specific deterrence to deter drink-driving and speeding, as research suggests that these behaviours are not deterred in the same way.

In a paper published by Warren Harrison and Nicola Pronk who were based at the Monash University Accident Research Centre in Victoria, Australia, they provided compelling explanations of the difference between the impact of visible drink drive and speed enforcement and summarized their findings as follows:

Police agencies often publicize their ‘general deterrence’ approach to reducing traffic offending and reducing road trauma. A singular focus on ‘general deterrence’ which is often focused on ‘highly visible’ enforcement is part of, but not the whole solution. It is important to recognize the need for both general and specific deterrence to deter drink-driving and speeding, as research suggests that these behaviours are not deterred in the same way.

In a paper published by Warren Harrison and Nicola Pronk who were based at the Monash University Accident Research Centre in Victoria, Australia, they provided compelling explanations of the difference between the impact of visible drink drive and speed enforcement and summarized their findings as follows:

The lessons that come from both this study and a range of others are that for a road policing deterrence strategy to be as effective as possible, it needs to:

Once again, as is the case with drink drive enforcement, there needs to be enough policing to drive down speeding. High volumes of random and unpredictable speed policing are required.

Dave Cliff, ONZM MStJ

CEO, GRSP

A total of 37 road policing officers and police leaders from Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Namibia, Uganda, and Romania attended the second Road Policing Executive Leadership Course 2022 (RPELC), offered through the Global Road Safety Leadership Course (GRSLC) suite of programmes.

This year’s RPELC was the first in-person course and was jointly delivered in October in Nairobi, Kenya, by the Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP) and Johns Hopkins International Injury Research Unit (JH-IIRU), with the support of Bloomberg Philanthropies Initiative for Global Road Safety (BIGRS).

A total of 37 road policing officers and police leaders from Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Namibia, Uganda, and Romania attended the second Road Policing Executive Leadership Course 2022 (RPELC), offered through the Global Road Safety Leadership Course (GRSLC) suite of programmes.

This year’s RPELC was the first in-person course and was jointly delivered in October in Nairobi, Kenya, by the Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP) and Johns Hopkins International Injury Research Unit (JH-IIRU), with the support of Bloomberg Philanthropies Initiative for Global Road Safety (BIGRS).

The six-day course showcased evidence-based road policing material developed by GRSP’s Road Policing experts, in line with the cultural context of attendees. Topics included current road safety trends, leadership principles, the role of enforcement in the Safe System approach, deterrence theory, legitimacy in policing, tasking and coordination, data collection, intelligence-led road policing, case studies, and the strategic alignment of mass media and public awareness campaigns with enforcement.

“We are extremely grateful for the opportunity to have attended this course. The content was well-researched and relevant to our different situations at home,” explained SP Boniface Otieno, a member of the Kenya Police Service and a dedicated participant.

The course also included a virtual conference conducted by Senior Transport Development Expert David Niyonsenga, member of the African Union, in which he discussed the road safety context in Africa and the role of the African Road Safety Observatory (ARSO). Transport Specialist Arif Uddin, from the Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) of the World Bank, also virtually joined as a presenter and outlined the intersection between enforcement and infrastructure improvements.

Participants were allocated into breakout working groups of seven throughout the course. This encouraged them to cultivate an atmosphere of camaraderie while brainstorming, collaborating, and sharing their own experiences.

With the aim of providing hands-on exercises, the RPELC offered a practical speeding and drink driving enforcement field activity in collaboration with the Kenya Police Service (KPS). GRSP’s Road Policing experts and KPS officers guided participants through a circuit of activities relevant to this type of enforcement operation.

“After this week, we will have some true champions from the policing community in these countries that we are working in. They will be able to effect real change on the ground and be leaders in their own jurisdictions. They will take home practical knowledge that they will be able to apply to their day-to-day jobs,” noted the Director of the JH-IIRU, Professor Abdul Bachani.

“We know that leadership in all walks of life makes an enormous difference. Leading and motivating people and explaining what works and what doesn’t work are critical features of road safety,” said GRSP’s CEO Dave Cliff. “Through changing road policing practice, we can make a difference, particularly in low- and middle-income countries in which the BIGRS is operating.”

GRSP and JH-IIRU’s staff congratulate all participants for the professionalism and enthusiasm they demonstrated throughout the week. Further, we extend our gratitude to the BIGRS for the support in the second delivery of the RPELC. We look forward to continue engaging with policing leaders in BIGRS countries to support strengthening of road policing activities.

During October, the Global Road Safety Partnership’s CEO Dave Cliff and Asia-Pacific Consultant Blaise Murphet joined international road safety stakeholders at the Global Regional Road Safety Observatories (GRRSO) Dialogue for Powered-Two-Wheeler Safety held in Manila. Co-hosted by the Asia-Pacific Road Safety Observatory (APRSO) and the Ibero-American Road Safety Observatory (OISEVI), the event assembled a wide array of experts and practitioners seeking to address deaths and injuries resulting from motorcycle crashes.

During October, the Global Road Safety Partnership’s CEO Dave Cliff and Asia-Pacific Consultant Blaise Murphet joined international road safety stakeholders at the Global Regional Road Safety Observatories (GRRSO) Dialogue for Powered-Two-Wheeler Safety held in Manila. Co-hosted by the Asia-Pacific Road Safety Observatory (APRSO) and the Ibero-American Road Safety Observatory (OISEVI), the event assembled a wide array of experts and practitioners seeking to address deaths and injuries resulting from motorcycle crashes.

After a variety of discussions by specialists from the World Health Organization (WHO), Towards Zero Foundation, Road Safety Observatories, Asian Development Bank (ADB), World Bank Group, FIA Foundation and others, the Statement of Participants produced a series of recommendations for enforcement and public health agencies, governments, road safety stakeholders and transport regulators.

One of the key recommendations was to set target dates for mandatory implementation of anti-lock braking (ABS) on all PTWs capable of travel speeds of 50km/h or greater. ABS has been shown to significantly reduce crash risk.

GRSP’s Participation

For his part, GRSP’s CEO spoke about the policing of powered two-wheeler (PTW) riders and passengers. He opened his presentation by quoting the Save Lives – a Road Safety Technical Package (2017) with which he stressed that strong and sustained enforcement of road safety laws, together with public education, can have a positive impact on the behaviour of road users.

He explained that road safety rules and effective policing are key components of the Safe System approach to improving road safety. For effective road policing to take place, the following elements must be integrated into the equation:

Clear and easily enforced laws such as motorcycle helmet-related laws, speed limits, random breath testing, registration plate visibility, and driver license-related restrictions are crucial areas that police officers should focus on.

Enforcement-Related Issues

While there are impediments to implementing effective road policing programmes, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021 – 2030 recommends the following:

“Establish a dedicated enforcement agency, provide training and ensure adequate equipment for enforcement activities.”

A few of the enforcement-related issues that police could encounter in PTW policing are the following:

Use of Protective Equipment

When it comes to reducing crash risk and severity for PTW riders and passengers, the use of protective equipment is of paramount importance. Highly visible and ideally reflectorised clothing will make it far more likely they will be seen by other motorists and vulnerable road users. Protective clothing will assist safeguarding riders and passengers from severe skin grazing in the event of a crash.

Mandatory wearing and fastening of a motorcycle helmet that complies with one or more of the approved international standards (riders and passengers) are imperative.

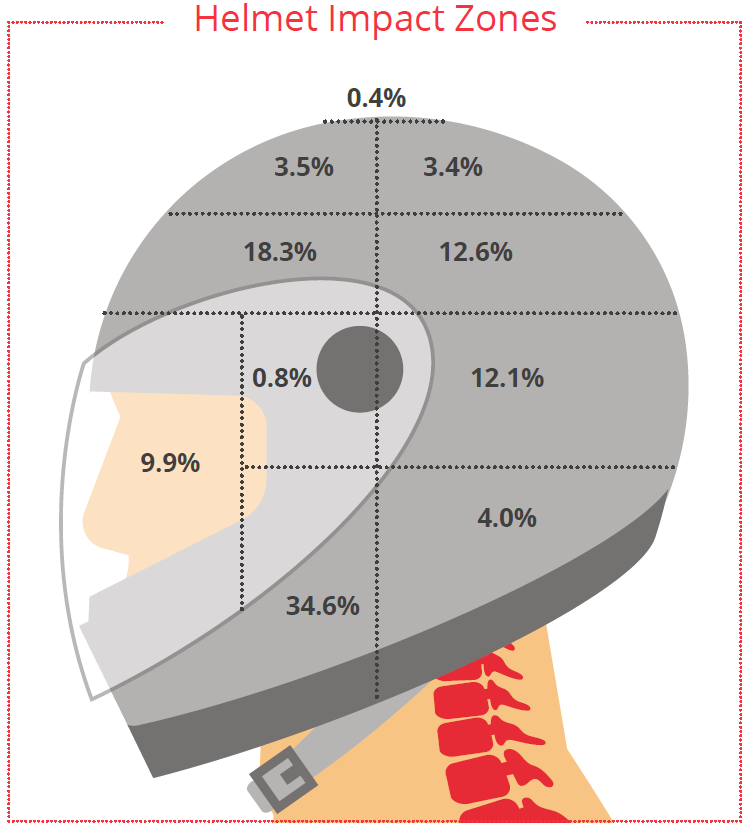

Motorcycle Helmets

In conclusion, and as the Powered Two- and Three-Wheeler Safety – a Road Safety Manual for Decision-Makers and Practitioners (2022) guide states, “implementation of such [PTW] interventions should take a comprehensive approach and be related to road users, vehicles and the road environment, using engineering, enforcement and education, and be applied in an integrated manner.”

An elemental component of a Traffic Police officer’s job is attending and securing the scene of a road crash. The quality of any subsequent crash investigation is highly dependent on the quality of the scene and evidence control applied. As there aren’t two crash scenes that are the same, officers must apply logic and common sense when securing a scene.

An elemental component of a Traffic Police officer’s job is attending and securing the scene of a road crash. The quality of any subsequent crash investigation is highly dependent on the quality of the scene and evidence control applied. As there aren’t two crash scenes that are the same, officers must apply logic and common sense when securing a scene.

Securing the Scene of a Crash to Ensure Safety means:

When officers receive a road crash call; they must gather the right data and ask for all the available information. It’s worth mentioning that a reduction in the interval between call time and response time increases the opportunity to secure evidence and identify witnesses.

Once officers arrive at the scene; they should observe the approaching traffic and think if any further emergency services may be required. The basic and essential equipment officers need when conducting an efficient crash investigation are exhibit markers, crash report forms, a notebook, a camera, a cell phone, and a tape measure. Nonetheless, it’s important to note that one of the most important tools an officer can take to the scene of a crash is a professional attitude.

When approaching the scene of a crash, officers must be careful and observant for pre-crash evidence. They must park in a place that will provide the most protection for everyone involved but which won’t disturb other emergency services. Additionally, they should occasionally run their engines if their vehicle’s flashing lights are on.

Protecting Evidence

Securing evidence while protecting the scene itself is an imperative step to take, as evidence found at crash scenes can be fragile. Setting up wide police cordons in all relevant areas will assist in protecting evidence.

Evidence includes elements such as scene measurements, photographing the scene, interviewing witnesses and suspects, and inspecting vehicles and official records, such as blood test results. Skid marks, vehicle debris, bloodstains, fingerprints, footprints, and glass fragments will assist throughout the investigation.

Contamination of evidence may take place due to the contact and exchange between people and things present at the scene. This concept, which aims to explain that every contact leaves its traces, is known as the “principle of exchange.”

Collaboration of Services

Firefighters

Towing Vehicles

Ambulance Crews

In the Absence of Appropriate Services and/or Equipment

Crash Investigation and the Safe System

Serious crash investigation is recognized as a specialized skill, with Traffic Police officers required to undergo extensive technical training. A few of the main objectives of conducting a crash investigation are to determine the level of responsibility of the person(s) involved, as well as the sequence of events and factors that led to the crash. By considering each component of the ‘Safe System’ approach, the investigator can assess what each part of the system played in the crash.

The ‘Safe System’ approach to crash investigation considers the speed (including the appropriateness of the speed limit), the road and roadside factors, the vehicle and road user factors that contributed to the crash.

For example, was the speed limit appropriate for the road environment and its use, what speed were vehicles travelling before the collision and what were the road and environmental conditions at the time. This will be helpful when developing recommendations to prevent further crashes from happening.

When officers commence a preliminary crash investigation; they must obtain accurate data regarding death(s), descriptions of all those injured, their injuries and demographics of people involved, whereabouts of suspects, and key contributing factors. Officers should establish the connection between the suspect and the crash.

Ultimately, one of the core components of a crash investigation is the search for truth in the interests of public health, safety, and justice. To get to the truth, officers must realize that the search of a crash scene should be as thorough as possible.

GRSP’s Crash Investigation and Reporting Guide (2021) states: “The investigating officer’s approach must be based on integrity and a sense of responsibility in accordance with community expectations. Their aim must be to objectively determine all the contributing factors involved in a crash, the details and injuries of all those involved, and report on it accurately and impartially. It also involves holding accountable any person who has committed an offence.”

With the assistance of Commisioner of Police (CP) Amitabh Gupta and former Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP) Rahul Shrirame from the Pune City Police and the support from the Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety (BIGRS), GRSP delivered the first in-person capacity building training in Pune, India.

The workshop was attended by 31 police leaders from across the Pune District—which included staff from Pune City, Pune Rural, Pimpri Chinchwad and Pune HSP. The workshop focused on promoting consistency in enforcement across the region. The Road Policing Capacity Building team conducted training in the following areas:

During the second day, the team trained a further 35 officers, all of whom learned about tasking and coordination, and accountability for performance. They engaged in interactive leadership exercises such as understanding road safety demands and risks in order to help them prioritize their enforcement focus.

The attendees shared their own experiences in enforcement and discussed how to implement the workshop’s content in their own areas.